A PhD in a pandemic

We’re often told that stress will get to pretty much every PhD student at some point. With the COVID-19 pandemic now in the mix, at times, it can feel and be paralysing. One PhD student’s tale about how COVID-19 is affecting early career ecologists.

Performance anxiety, imposter syndrome, relationship issues – they can mount up, especially in relatively new researchers within intense academic environments. PhD students with important fieldwork aspects, like many of us in ecology, are often under other pressures. For example, designing and implementing field methodologies for which there may be virtually no pre-existing blueprint; having to change designs mid-way due to some unforeseen factor; navigating tough terrain, tropical weather systems, hostile flora and fauna.

For me, all these factors were causing anxiety and stress, when the global coronavirus pandemic struck. Alongside generating new societal uncertainties and worries about the health of loved ones, the pandemic exacerbated existing anxieties and the associated fears of failure.

My fieldwork takes place on the idyllic Round Island: a 2.5 km2 volcanic island located 21 km north of Mauritius, and one of the last remaining patches of native palm forest in the Mascarene Islands. It’s uninhabited, except for a few conservationists. Though certainly a paradise, Round Island can be tough on the body and mind. My sampling, for example, involves navigating to randomly-generated quadrats over razor-sharp slippery rocks or chest-high spikey weeds (Cenchrus echinatus) whilst carrying a 5kg leaf-blower and 5kg backpack in 30oC+ heat. This can be a little sketchy, even in the dry.

For five days, us four resident conservationists were waiting for a helicopter evacuation because of an incoming cyclone. The evacuation eventually came on Sunday, March 15th. During the wait, we read about the ever-escalating threat of coronavirus but it was an abstraction – a distant problem for another day.

Our bubble was about to burst

I got back to the Mauritian mainland on Sunday afternoon. Mauritius at the time had no confirmed cases. We thought we might get back onto Round Island on the Wednesday but, alas, the situation developed rapidly and our bubble was about to burst.

The effects of COVID-19 were now widespread in Europe and becoming much worse. More and more countries began closing their borders, restricting travel, and freezing airlines. Cases of coronavirus were increasing exponentially. Prevention measures were insufficient or dangerously delayed.

By Tuesday, I knew I had to get back home very soon. There was a risk that if I left it too late to get a return flight that I would be stranded in Mauritius for months. However, there was some hope: the helicopter trip to Round Island the next day would mean I could hop on, grab my samples and personal items, and escape. At the last moment, on Wednesday morning, a fellow researcher staying in the house became symptomatic and the trip was cancelled.

The National Parks and Conservation Science Service had 3 minutes to get my stuff off the island

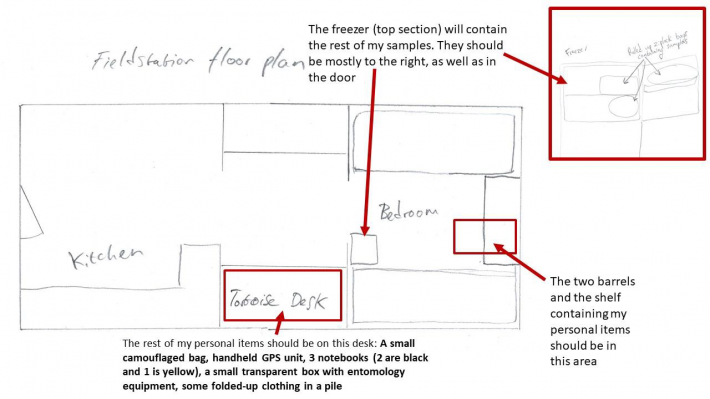

Everything moved so fast. On Wednesday afternoon, the government began preparations to send several caretakers to Round Island by helicopter on Friday. Suddenly, we now had time to get my samples back before my flight in the evening of the same day. I had 90 minutes to send some clear instructions to the National Parks and Conservation Service for getting my stuff off the island within 3 minutes. I hurriedly began drawing and scanning and annotating, eventually coming up with the best piece of work my PhD will ever see.

Then, disaster: on Thursday morning my fine graphic design work was rendered obsolete. Government were now no longer heading to Round Island. Mauritius had three confirmed cases of COVID-19.

Thankfully, with amazing support, prompt replies, and excellent advice from my supervisors, university finance team, and staff within the School (thank you Janet, Pete, and Jim), I was able to buy a flight for Thursday.

The situation in Mauritius was getting worse, and the ever-changing situation demanded new plans every few hours. It was emotionally and mentally exhausting for us all. On top of that, I was devastated to leave without my hard-earned samples and personal belongings.

Finally, I was on a flight back to the UK. Although drained, the journey gave me time to reflect on some of the chaos.

The COVID-19 pandemic has forced some existing fears into reality

The gravity of the situation for PhD students is enormous, especially for those with important fieldwork still to do. Anxiety about failing to get enough or the right samples, what that might mean for the project and how this affects the PhD are common fears in relatively untested field ecologists who may be on their first trip of this sort. The COVID-19 pandemic forced some of these fears into reality for some of us.

I have exceptionally supportive colleagues, supervisors, friends and family, but even so, I’ve felt high stress levels regarding my PhD work. Ecology brings us to fabulously tough places. For many of us, myself included, our fieldwork seasons are some of the first big field projects we’ve developed and run ourselves. These situations are already high-pressure.

None of us know what it will mean for our projects

Lockdown then enters the mix and prevents PhD students from continuing with work that needs to be carried out at university. Other students and early career ecologists whose fieldwork was cut short suffer this anxiety as well. At this stage, none of us know what it will really mean for our projects.

But it’s not all doom and gloom. There is much hope to be had from how people are coming together during this pandemic and how we can use that collective behaviour to tackle other global issues. But it is important to check-up on the newer ecologists amongst us. The situation is overwhelming at times and we need all the help we can get from the community.

Like what we stand for?

Support our mission and help develop the next generation of ecologists by donating to the British Ecological Society.