Migratory bats tracked for the first time ever, using new algorithm

For the first time ever, researchers can track the movements of bats with the help of a brand new algorithm utilising radar technology, created by the University of Haifa and Tel Aviv University.

A new study, published in Methods in Ecology and Evolution, reveals that bats migrate across the globe just like birds. However, their migration patterns are vastly different.

Thanks to a new algorithm, now available to researchers worldwide, we can now monitor the movement of bats in the vicinity of wind turbines. In turn, this will allow for the development of new methods for protecting bats – who currently die at a rate of up to ten times that of birds due to lack of available data surrounding their flight patterns.

PhD student and lead author of the study Yuval Werber explained “The use of wind turbines is increasing worldwide. Their ability to operate in an environmentally friendly way depends on their impact on winged creatures.”

Until now, a knowledge gap surrounding the movements of bats near turbines led to a lack of effective methods for lowering their high mortality rate.

“People around the world can now track and monitor bat movements, thus saving many of them,” continued Werber.

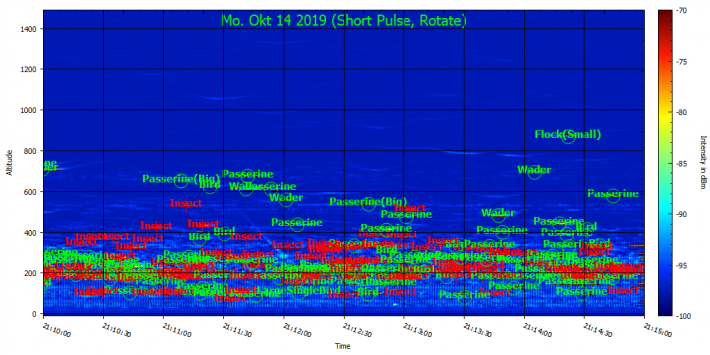

In recent years, the use of radar to research airborne species has become increasingly common. Radar provides data on size, flight speed, body structure and pattern of wing flapping for flying animals. This data enables researchers to examine basic ecological issues at unprecedented scales. Data vital for infrastructure and development projects can now be provided to avoid interference with wildlife flight paths.

What stopped radars from tracking bats before now?

In order to develop an algorithm capable of identifying bats, there is a need for human observation. Since bats mainly fly at night and at high altitudes, it has been impossible to collect verified data about them. Without data, nobody could develop an algorithm capable of bat identification.

As radars are often part of preliminary ecological surveys before major construction projects, many structures have been built without taking bats into account.

So how did the researchers get around this issue? Using a network of bird radars across Israel, researchers identified a particular two week period in June where there was no night-time activity from migrating birds across the Hula Valley region in Israel. By process of elimination, any observation during this period that is not an insect, is likely a bat.

These bat observations were isolated according to activity times, the biomechanics of their wing movement, and the size of the creature. Then, by using the database from the already established bird radars, the researchers created an algorithm capable of distinguishing birds from bats.

Validation tests for the algorithm showed an accuracy of over 90 percent. “Thanks to the algorithm, we now have a unique global database of 60,000 bat observations.” exclaimed the team.

How does the new algorithm aid bat conservation efforts?

With the help of the remarkable database, it is now certain that bat migration shows distinct differences to bird migration. Bats begin to migrate later than birds in both migration seasons. They also migrate at a much lower height (200-600 metres), compared to birds (between 100-1000 metres).

“Millions of bats die each year due to the operation of wind turbines. Unfortunately even non-polluting energy sources can have serious ecological ramifications,” said Werber. “The use of our algorithm worldwide will facilitate study of the environmental factors affecting bats. We can further our knowledge of their behaviour, and the possible impact of climate changes on numerous bat populations across the globe.”

Article inspired by a University of Haifa press release.

Read more here:

, , , & (2023). BATScan: A radar classification tool reveals large-scale bat migration patterns. Methods in Ecology and Evolution, 00, 1– 16. https://doi.org/10.1111/2041-210X.14125

Like what we stand for?

Support our mission and help develop the next generation of ecologists by donating to the British Ecological Society.