Understanding the decline of Atlantic salmon catches in Scotland

Annual catches of Atlantic salmon have declined steeply since the highest recorded level in 2010. We invited an expert in salmon ecology from Marine Scotland Science to explain why this may be happening.

Atlantic salmon are one of Scotland’s most iconic species, forming an important part of river ecosystems and, through salmon fisheries, making an important contribution to the rural economy. Atlantic salmon live in fresh water as juveniles before migrating to sea to undertake long migrations to their oceanic feeding grounds in the North Atlantic. As adults they return to the rivers in which they grew up where they then spawn and begin the next generation.

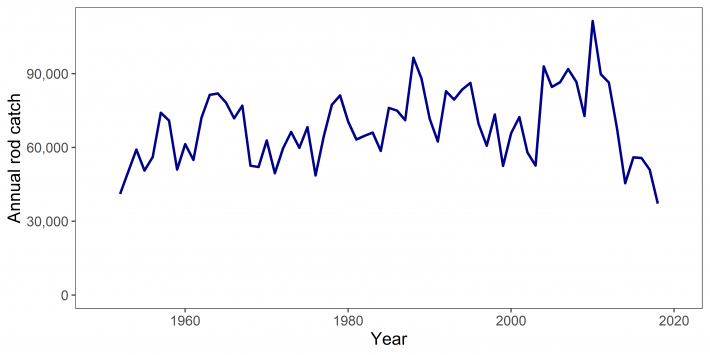

The Scottish Government has collected, and published, the catches of wild salmon reported by rod fisheries each year since 1952. Annual catches have declined steeply since the highest recorded level in 2010. The catch in 2018 was the lowest recorded being 33% of the 2010 figure, and 67% of the previous 5-year average. Although the scale of the decline in 2018 was undoubtedly influenced to some extent by adverse fishing conditions due to the prolonged dry spell of weather, the general pattern of decline was seen in other catch-independent metrics from fish counters. Furthermore, the pattern was mirrored in other countries, highlighting that low catches in 2018 reflect continuation of a real decline in salmon numbers.

Figure 1: Reported rod catches of salmon in Scotland 1952-2018.

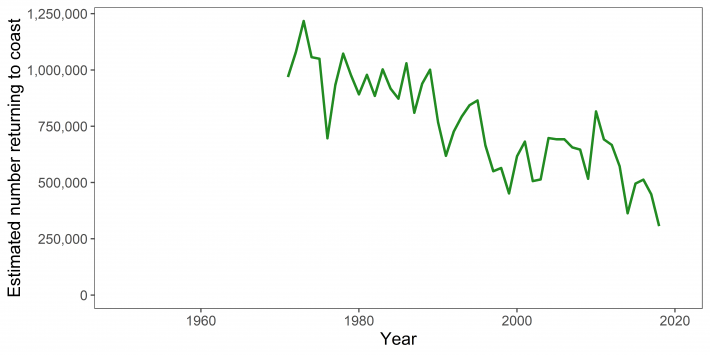

Rod catches tell only part of the story, and the pattern of decline is best illustrated by considering the numbers of salmon coming back to the Scottish coast from their oceanic feeding grounds (Figure 2). These data illustrate a longer sustained reduction in numbers than is apparent from rod catches. Previously managers could counteract these declines by reducing the number of net fisheries operating on the coast (compare the decline in returns to the coast [Figure 2] with the numbers captured in rivers [Figure 1]). However, with cessation of coastal netting this buffering capacity has now been fully used. Furthermore, additional protection for stocks through release of salmon caught in the rod fishery is now at 93% with little further scope to compensate for the decline in numbers of returning fish by restricting retention.

Figure 2: Decline in the estimated number of salmon returning to the Scottish coast. Data are taken from the International Council for the Exploration of the Seas Working Group on North Atlantic Salmon.

Atlantic Salmon face a number of pressures throughout their lives both in fresh water and in the marine environment. Whereas freshwater factors can be important for some salmon populations the range-wide decline is thought to be related to changes in the marine environment. A recent international study used a sophisticated population model to highlight evidence of a decline in marine survival common to stocks of salmon throughout the North Atlantic over the period 1971-2014.

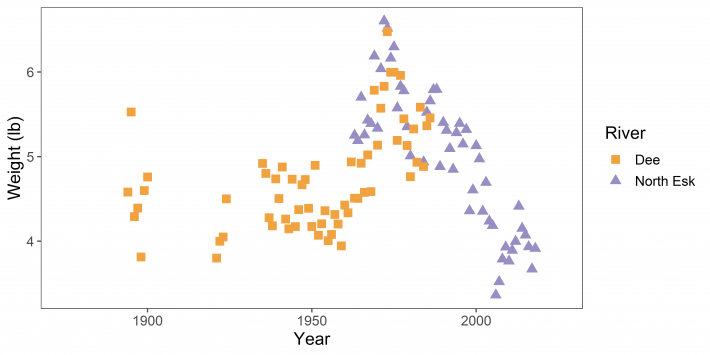

Not only are fewer salmon returning to rivers but those that do come back are smaller than they were in the 1970s.

It is the number of eggs produced by spawning salmon rather than only the number of spawners that determines how many salmon will be produced in the next generation. The reduction in the size of returners therefore exacerbates the problems caused by declining numbers of salmon returning to the rivers to spawn. Historic records of the sizes of salmon caught in fisheries show that the sizes of fish have fluctuated in the past although, like survival, the mechanisms underlying such patterns are unclear (Figure 3).

Figure 3: Changes in the weight of salmon caught in commercial netting on the Rivers Dee and North Esk. Data are shown for salmon which had spent one year at sea and were subsequently caught during July.

A number of studies have implicated climate change as the driver behind recent changes in growth and survival of salmon at sea. However, the underlying mechanisms are unclear but may, for example, result from changes in the distribution of predators or prey.

Much of the life of salmon at sea remains poorly understood, and therefore management efforts have focussed on those factors that can be controlled. For example, in 2016 in response to concerns about the state of stocks, the Scottish Government introduced a prohibition on the retention of salmon in coastal waters and allowed salmon to be removed by fishermen only in rivers where stocks had been shown to be meeting conservation targets. Currently the Scottish Government is examining a number of high level pressures impacting on salmon to identify the potential for further management actions. Similar work is being undertaken in a number of countries.

In common with Atlantic salmon populations, there are also concerns over the status of many of the Pacific salmon species. These concerns are highlighted by 2019 being designated the International Year of the Salmon. This initiative, led by the North Atlantic Salmon Conservation Organization (NASCO) and the North Pacific Anadromous Fish Commission (NPAFC), aims to raise awareness and understanding of the social and economic benefits that salmon provide, and the many issues facing salmon around the world. The initiative aims to bring people together to share and develop knowledge more effectively, raise awareness and take action.

Like what we stand for?

Support our mission and help develop the next generation of ecologists by donating to the British Ecological Society.